From 1972 to Present: Okinawa in Contemporary Japan

Contents

Media and Broadcast

The government had been encouraging the unification, especially culturally and linguistically, within the country since the Meiji period. The desire of promoting the nationalist ideologies and Standard Japanese was shown even greater during the wars, as the one could be executed if caught using Okinawan (Heinrich, 2004: 161). During the war period, the Okinawan elements and perspectives were totally left out in the mainstream Japanese media (Tanji, 2012: 113). The mass media had been an essential tool for the central Japanese government to promote the ideas and language from Tokyo, and the official media did not pay too much attention on the local culture and language, Uchinaaguchi.

In the meantime, the Japanese media helped shorten the distance between Okinawa and the Japanese. National broadcasting institution NHK had conducted a survey in the middle 1960s, more than half of respondents indicated that there is a major effect on the spoken language regarding to the language use in broadcasting, which allowed them to understand Standard Japanese more easily (Carroll, 2001: 10). Therefore, the media could help the locals to perform code-switching with less effort according to the circumstances, which would reduce the difference between Uchinaaguchi and Standard Japanese, but more possibly transform transform Uchinaaguchi towards the standard language (ibid).

Later, with the growing respect to the dialects from the Japanese government (Gottlieb, 2011: 8), Okinawan culture and languages have been gaining back the importance in the mainstream Japanese media and broadcasting. NHK had produced a TV programme that incorporated with Okinawan culture. The programme was named "Ryukyu no kaze" and was broadcasted nationally between 1992 and 1993, celebrating the 20th anniversary of the return of Okinawa to Japan, and an Okinawan version was even produced by the Okinawa branch of NHK in 1994 (Hara, 2005: 197). Also, the Okinawa branch published the Okinawan translation of the national classic novel "I am a cat" which is written by the famous writer Natsume Sōseki (ibid). This reveals that the mass media, the audience, and the government was getting interested in the unique culture of Okinawa, and the language behind it.

Recently within Okinawa Prefecture, there are many local media and broadcasters that are active in producing programmes promoting the local culture of Okinawa and the traditional Uchinaaguchi. Some prefecture-wise radio broadcaster, like Radio Okinawa (also known as ROK) and FM Okinawa, and local television broadcasters, for instance Ryukyu Broadcasting Corporation (RBC) and Okinawa Cable Network Incorporation (OCN), are popular among the public in Okinawa (Galan & Heinrich, 2010: 54). There are also many community broadcasters like FM Taman, which are also the advocators of the local culture. Responding to the great effort from the broadcasters to preserve the traditional culture, the audience and the public is actually attracted and inspired by their productions. Some of the programs consisted of receiving audience’s message and commenting those messages during broadcast (Galan & Heinrich, 2010:56) This kind of interactive experience induce further discussion in topics related to Uchinaaguchi and participants became more aware of those local languages (ibid). For instance, an audience from Tokyo keep following the programmes because they are interested in learning more about Uchinaaguchi and he started to use Uchinaaguchi expression when talking to Ryukyuan. (ibid). Meanwhile, the local broadcastings are having an attempt to transform into cross-media broadcasting, with the help of the Internet and communication technology, and extend their influences and the promotion of Okinawan culture further, even overseas (Galan & Heinrich, 2010: 60).

Self-esteem and Language

The usage of Uchinaaguchi nowadays varies a lot from district to district in Okinawa. Local identity as an Okinawan plays an important role on determining the choice of language. It is believed that one of the major factors contributing to identity is the social status of their ancestors. Okinawan with ancestors of higher class would tend to preserve and speak Okinawan language (Osumi, 2001:74). Nakijin was a castle town residing the warrior class and merchants in the past (ibid) According to Osumi, a villager in Nakijin was one of the most fluent speakers of Uchinaaguchi in his age group (ibid). It is believed that the historical heritage left in the village helped to retain his Okinawan identity and the language was maintained due to the higher social status of his ancestors. Parents in Nakijin were more willing to taught their offsprings Uchinaaguchi and encourage their children to speak Uchinaaguchi (ibid). On the other hand, the situation in Ogimi was the exact opposite of Nakijin. According to a local villager, everyone in the village tried hard to speak Japanese (Osumi, 2001:75). People of Ogimi thought Central Okinawa was inferior to standard Japanese and hence force their offspring to speak proper Japanese (ibid). Although the conversations between the older generations still use Uchinaaguchi, they tried to use standard Japanese to communicate with the youth.

From the above examples, the use of language is closely related to the social status of their ancestors and their current economical or social opportunities. the attitude of the parents determines what their children learn. Regions with more understanding on the historical background of Okinawa or obtained a higher social status can speak better Uchinaaguchi .

Okinawa boom

While the loss of Uchinaaguchi seems to be inevitable in the next generation, many cultural organizations started to promote the traditional Okinawa culture and language, and the efforts gave huge contribution to the "Okinawa boom" in the 1990s (Hara, 2001:197).

The start of (revitalizing) cultural activities could be traced back to the 1950s. In 1955 in the light of the decline in cultural activities in Koza City (or Okinawa City), the pioneer of these organizations, which is the Koza Cultural Association, was established (Hara, 2001:195). There were many similar associations founded later throughout the Ryukyu islands and were merged into Okinawa Cultural Association in the prefecture level (ibid).

Many activities were then held to raise awareness on Uchinaaguchi. For instance, the first dialect contest was held in 1993 in Yomitan (ibid). The whole contest was held in Uchinaaguchi including the sponsor’s speech and the chairman’s speech (ibid). Another example was the Murashibi which was a traditional village festival. Traditional Okinawa opera (Kumiodori) and traditional opera (Kyogen)was performed based on Buddhist and Shinto culture.(Hara, 2001:196) The festival was suspended during the second world war, but the revival process started in 1955 in Yomitan and then spread to 14 other districts nowadays (ibid). The Uchinaaguchi is an important part of the festival and the festival provide a cultural background for some other activities (ibid). The Grand Prix of Ryuka, which has begun in 1991, would also be an unique campaign organized in Okinawa, and it requires contestants to write the traditional Okinawan poem Ryuka, which is composed of stanzas that take form of the special 8-8-8-6 syllables pattern (ibid). The Grand Prix demands a great manipulation of Okinawan languages from the participants in order to create a beautiful piece of traditional poem.

These activities create opportunities for both the locals and the foreigners to experience and appreciate the traditional culture and language in Okinawa. At the same time, this reveals the intention of the locals to revive the endangered culture and language, and efforts were made for reviving from the community level.

Current usage of Ryukyuan languages

(Heinrich,2004:155, Table 1)

The above table shows the current status of Ryukyuan languages, including Central Okinawan Language. The prevailing language in Okinawa is the local variety of Standard Japanese, with all the young speakers using the local Japanese dialects in daily life. Noticed that there are no young speakers of Ryukyuan, and the languages are on the road to extinction.

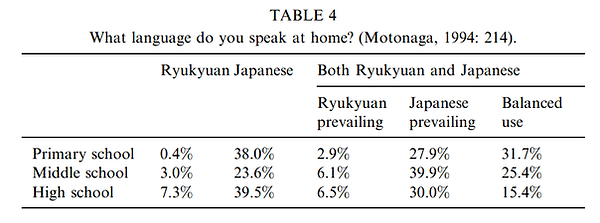

(Heinrich,2004:170 Table 4)

The above table showed the situation of Ryukyuan language in domestic functions. Central Okinawa Language, as the major Ryukyuan language, failed to pass to the next generation as shown in the table. Majority of primary school students use either only Japanese or mixture of Ryukyuan and Japanese as the language of communication at home while few only use Ryukyuan at home. The result can be explained by a similar research conducted by Osumi. Osumi conducted a survey on students in Okinawa in 1996.(Osumi, 2001: 77) The result of the survey showed that majority of the respondence believed that “I am interested in Okinawan and want to learn it if I could” but they thought “Okinawan is the language of the elderly people” and “We had better learn standard Japanese rather than Okinawan” (Osumi, 2001: 78) This showed that the next generation no longer saw Central Okinawa as a common language of communication but an additional knowledge that is optional.

Another question from the survey reviewed the current mindset of the students in the Japanese society. The question asked the respondence what was their opinion on current usage of Uchinaa-Yamatoguchi (Osumi, 2001: 79). Majority of the respondents concerned about the bilingualism will harm the accuracy of standard Japanese while some even believed that Okinawan used by the youth was not correct and they should learn standard Japanese instead (ibid). Hence the next generation generally believed Central Okinawa has no use and it will only confuse and interfere the learning of standard Japanese.

Respect from the Government

Although the assimilation policies, which were mostly enforced since the Meiji period, had been greatly influential, probably in a negative manner, to the vitality of the dialects in Japan, it also drew the attention of the public to the disappearing dialects (Carroll, 2011:11). In response to the concerns of the public, the language planning policies seemed to be loosen since the 1960s (ibid). Though Uchinaaguchi, similar to other dialects all over the country, was suppressed and banned strictly before, the government made changes in educational policies. For instance, the importance of contact with the standard language was still emphasized in elementary schools in 1968, but related policies were kept modifying and eventually students were taught to switch between the local language and the standard language according to different occasions about 20 years later (ibid). In 1998, it is clearly stated in the “National Curriculum Guidelines for National Standard Language” that secondary students are required to gain the ability to “distinguish between dialect and Standard Japanese”, and the ability to understand “the different roles of the standard and the dialects in sociolinguistic terms” (ibid). The government gradually accepted the use of Uchinaaguchi in Okinawa, like the government did to the other dialects.

In the 1990s, even government institutions began to accept the existence and value of the other languages in the nation. In 1995, the National Language Council, which was responsible for managing the national language policy, addressed in the report that the local languages are “valuable in their own right and worthy of maintenance alongside the Standard” (Gottlieb, 2011:7). The highness of Standard Japanese maybe unchanged, but the local dialects were having a higher ranking. In the same report, it appreciated the effort made by the National Institute for Japanese Language on researching and mapping dialects in the state (ibid). Dialects like Uchinaaguchi were believed to possess some unique characteristics which could add some richness to the national standard language.